He was the youngest of seven brothers and said, “We had a very difficult time. Life was tough.

“I remember my mom worked at a sandwich store and when she left the job at the end of the day, she’d bring home the leftover pieces of bread, and I’d eat that. I’d make toast out of it and that would be my breakfast.

“I always said to myself, that if I ever got a good job and did well, I was going to try to do whatever I could to help people who had the same kinds of problems I had.”

Thanks to a stellar football career – first at the University of Louisville and then with the powerhouse Cleveland Browns of the 1960s – and then through his partnership here in Dayton with Sam Morgan to form the ultra-successful Ernie Green Industries, he did do quite well.

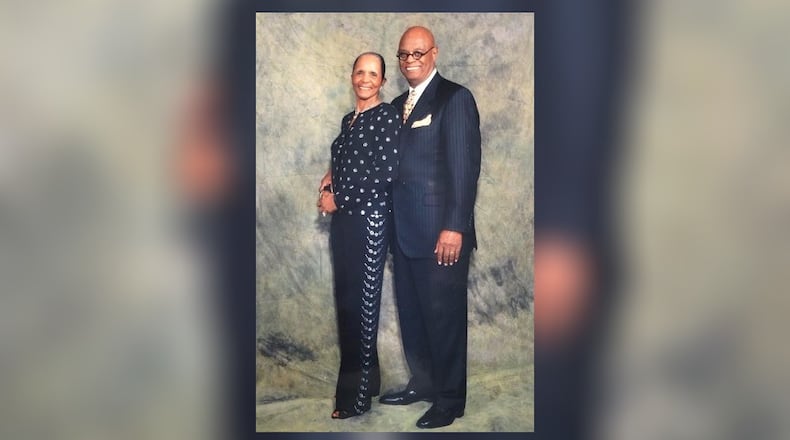

And with the side-by-side assistance of his dynamic wife, Della – whom he married in 1996 – they have become a philanthropic force all across the Miami Valley:

- Friday morning – as part of the gala festivities leading up to Saturday afternoon’s Homecoming Game against Morehouse College at McPherson Stadium – Central State will honor the couple when it names its newly-renovated Foundation I residence hall the Ernie & Della Green Hall.

Although the Greens are not alums – Ernie went to Louisville and Della is a Fisk University grad – they not only have provided financial support for many ventures on the CSU campus, but they have served on various boards at the school.

And when Ernie was President of the Foundation Board, he played a role in the resurrection of the once-glorious football program, which was shut down from 1997 through 2004.

“We love this university and what they are doing,” Della said. “We consider Central State to be a great HBCU and we’re proud to be part of the CSU family.”

- The Greens – named the area’s “Outstanding Philanthropists” in 2010 and honored at the Schuster Center as part of the National Philanthropy Day ceremonies – have aided everything from the Dayton Boys & Girls Club and the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company (DCDC) to the American Red Cross and the Dayton Urban League.

- This being National Breast Cancer Awareness Month, the Greens not only have provided financial backing to the cause, but Ernie has been a willing spokesman after surviving a 2004 diagnosis of breast cancer that required seven years of treatment.

The disease has devastated his family. He said his mother, Susie Kate, and several of her eight sisters had breast cancer, as did his own two sisters, a niece and a cousin.

Because many people still don’t realize the disease also is a threat to men – and some males treat it as a stigma and stay silent about it – he has spoken out and uses his own story to educate and encourage men to get checkups and treatment.

- Just recently the Greens returned from Columbus, Ga., where they have started a scholarship fund for students from Ernie’s old neighborhood who want to go to an HBCU, but need financial assistance.

They started the Ernie and Della Green Scholarship Program a year ago and already have three students attending Prairie View A&M in Texas, Della said. Their latest trip was to review candidates for next year’s scholarships.

“Ernie and I believe in the importance of service and giving back to the community, especially when young people are involved,” Della said.

Ernie agreed: “I look at some situations and when I know we did some things to help, some things that can make a difference in someone’s life, it just tickles my heart.”

Lombardi was right

Sports provided Ernie the path to better times.

He attended Spencer High School, then an all-black school in Columbus, and he wasn’t only a multi-sport standout, he was in the National Honor Society and served as the senior class president.

He led the school to a state football title in 1956 and a state runner-up finish a year later. His jersey number would eventually be retired and recently he was enshrined in the Georgia High School Football Hall of Fame.

Although Columbus is in the heart of Southeastern Conference country, SEC schools wouldn’t start adding black players to their football rosters until eight years after Ernie graduated high school in 1958.

Eventually, he said, a representative of Louisville – one of the only schools below the Mason Dixon Line which would take a black player then - reached him by phone and offered him a Greyhound bus ticket and a chance to play.

Before he left, Ernie said his no-nonsense mom – “She didn’t play,” he chuckled – gave him two pieces of advice:

“Keep your nose clean…And don’t come home!”

He said he boarded a bus at 5 a.m. and rode over 12 hours to get to a city, a school and a team he did not know.

When he got there that evening, no one was there to pick him up and, briefly panicking, he considered returning home until he remembered his mother’s warning.

Instead, he called the coach – who said he’d forgotten he was coming – and finally got a ride to the Louisville campus, where he lived in a barracks used for police officer training.

He ended up starring in football – he led the Cardinals in rushing two seasons – and baseball, where he was a third baseman who caught the eyes of pro scouts.

Unfortunately, at some stops, he also caught the attention of bigoted fans who didn’t like seeing a black player. He once recounted to me a game Louisville played at Eastern Kentucky University.

He played third, the bleachers weren’t far away, and he said the taunts were non-stop:

“I was the only player of color, and they called me everything but a child of God.”

Like always, his play on the field was his pushback, and by the time he was preparing to leave Louisville, talent evaluators agreed he could play either football or baseball professionally.

“Baseball would have meant going to the minor leagues first and I needed the money,” he said. “I didn’t have two quarters to rub together.”

The Green Bay Packers drafted him in the 14th round in 1962, but after he played well in the first two preseason games he said he was told to report to Coach Vince Lombardi’s office.

When he got there, he said Lombardi told him to relax. He wasn’t being cut.

Lombardi was good friends with Cleveland Browns coach Paul Brown, who had drafted Heisman Trophy running back Ernie Davis out of Syracuse.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

The overall No. 1 pick, Davis was diagnosed with leukemia, and it looked as if he’d never play football again. At the time, no one fathomed Davis would die in less than 10 months.

“Coach Lombardi said, ‘Paul Brown needs a running back and we think if you go to Cleveland and do what we’ve seen you do here, you can play in this league,’” he said. “He shook my hand and said, ‘Good luck!’

“And from that day until he retired, every time we played the Packers, Coach Lombardi made it a point to find me and say hello. He was one of the greatest coaches who ever lived, and he was that kind of guy, too.

“I just absolutely adored him.”

And Lombardi had been right.

Ernie could play.

He spent seven years in the NFL before his career was cut short by knee surgery after the 1968 season. He was selected to two Pro Bowls, the Browns won the NFL championship in 1964 and in 2012 he was enshrined in the Browns Legends Association.

While he rushed for 3,204 yards in his career, had 2,036 receiving yards and scored a combined 35 touchdowns, he was best known as a superb blocker for Cleveland’s celebrated backs: Jim Brown and then Leroy Kelly, both of whom would end up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

You could call it football philanthropy – he said the other day “it’s just being a good teammate,” – but with Ernie helping bulldoze the way, Brown rushed for a then-NFL record 1,863 yards in 1963.

After Brown retired, Kelly took over and, often running behind Green, he led the NFL in rushing in 1966 and had three straight 1,000-yard seasons.

After his retirement, Ernie coached a season for the Browns, then was an assistant vice president at Case Western Reserve and served as the executive director and VP of IMG’s Team Sports Division.

In 1981 he teamed up with Morgan – whose older brother Jim had been a basketball stalwart at Louisville – and launched EGI, which manufactured components for automobiles, healthcare, energy and other industries.

Before being sold in 2023, the company had expanded to 11 plants in six states, as well as Canada, the Dominican Republic and China.

Ernie first saw Della at a golf course in Cleveland in the 1990s. Trying to strike up a conversation with her, he asked her what her name was and – as he now laughingly remembers – “She told me it was none of my business!”

In the coming months, the more he found out about her the more impressed he was.

She was raised in Memphis and urged to go to Fisk, the HBCU in Nashville, by her father, who had been a paratrooper in World War II.

He was part of the U.S. Army’s 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the historic all-black unit known as the Triple Nickels.

After Fisk, Della came to Cleveland where she taught grade school, then became one of the most prominent school administrators in the Cleveland Public Schools system.

She had no idea Ernie had played football or that, as a friend finally told her: “He’s just the nicest man! Everyone in Cleveland loves him.”

She gave him another chance, they clicked and married. With their blended family, they had four boys.

Here in Dayton, Della and Ernie became pillars of philanthropy.

More importantly, she became the backbone he needed when he was blindsided by the breast cancer diagnosis – “I couldn’t breathe when I first heard the words,” he said – then was told he needed chemo treatments and a mastectomy.

Just as he had once bulldozed defenders out of the way for Brown and Kelly, she pushed aside his fears to get him through treatment and into remission.

Answering the call

Ernie said former CSU president John Garland first reached out to them and asked them to support the university.

“We were honored to be asked,” Della said.

The more familiar they got with the school and its students, the more they not only opened their checkbook, but rolled up their sleeves and pitched in on campus.

Della – who has had similar positions with the American Red Cross and the Boys and Girls Club – was on CSU’s Board of Trustees for a dozen years and was chair of the academic committee and the nominating committee.

Ernie was similarly involved and in 2011 the school honored them in a Schuster Center gathering that included award-winning actress Taraji P. Henson, an HBCU grad of Howard University.

“We do this because we consider Central State a great HBCU,” Della said.

As an educator her whole life, she said she’s taken special interest in the CSU instructors and especially the students: “We are so proud of them.”

She especially praised the business school, the engineering and manufacturing programs and the ROTC program.

She said seeing them succeed and prosper underscores their commitment: “We will continue to answer the call. We feel good helping others.”

And that “tickles” Ernie’s heart.

About the Author